The Isle of Man in Epic Imagination

Wed, 02 Feb 2022

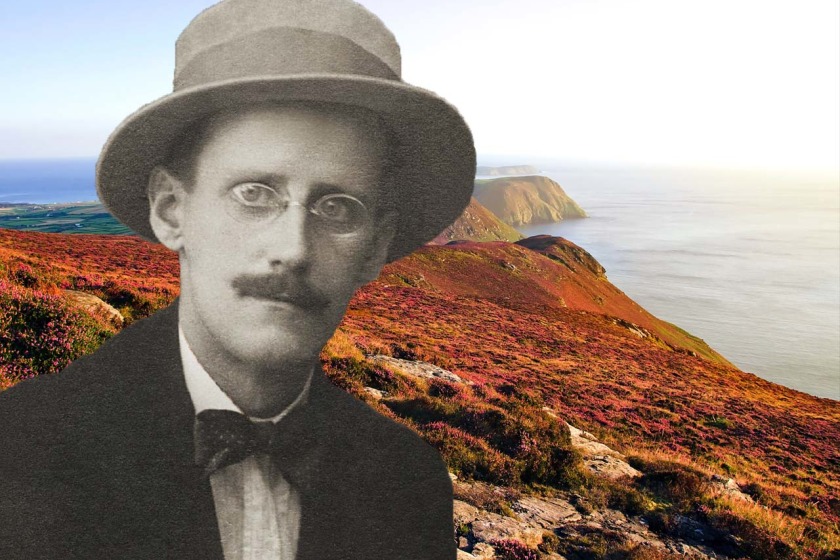

James Joyce's great novel, Ulysses, was first published 100 years ago, on 2 February 1922.

Few people realise the number of references to the Isle of Man and Manx matters within this great work of modern literature, so it is worthwhile to use this 100th anniversary to offer Simon Collister's excellent essay on the subject here.

His essay offers not just a reading of the Isle of Man's place in the great Modernist novel, but also its place within Joyce's wider thinking, in the earlier and contrastng Moby Dick by Herman Melville, and it offers suggestions of how we might reflect on the Isle of Man and what it is to be Manx today...

Enjoy!

The Isle of Man in Epic Imagination

An essay by Simon Collister

As a Manxman away from the Isle of Man’s shores it’s not uncommon to contend with conversations diminishing the Island or its position in the modern world.

The TT….. the Fairy Bridge, cats with no tails….. Set your watch back 50 years.

We’re used to it.

But we shouldn’t be.

There was a point in history when the Island was seen as a unique and influential nation occupying an important place – physically, historically and politically – in the modern world.

While these days we expect most people not to have heard of the Isle of Man, for some of the most important writers of the twentieth-century the Island was a source of inspiration. Partly due to its ancient and historically unique democracy, its status as a British colony which achieved had Home Rule or its embodiment of a modern, consumer-led economy the Island contained a significance from which towering literary giants, Herman Melville and James Joyce, used as central themes as they wrote into existence the futures of their own embryonic nations.

I want to suggest that when it comes to the future of the Isle of Man we can do a lot worse than looking back at the twentieth-century’s greatest literature to learn about how the Island was perceived and ask the question: have we fulfilled the expectations set in the early days of modernity – and if not, what can we do to reclaim the Island’s status as a central force for political and cultural innovation.

Moby Dick and The Manx Captain

Although not initially well received when it was published in 1851, Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick; or, The Whale has since been hailed as one of the Great American Novels.

The story at the heart of the novel – famously recounted for most of the book by Ishmael – tells how the infamous Captain Ahab assembles a ship’s crew to take part in his personal quest to hunt down Moby Dick, a rare white sperm whale, whom Ahab has encountered before.

As the journey progresses Ahab’s character becomes increasingly obsessed and erratic leading his crew into danger. Suffused with mystical and spiritual symbolism, the voyage culminates in a final showdown with the eponymous whale.

The book is hailed as one of the Great American Novels for its portrayal of a multiracial ship’s crew drawn from nations all over the world, the way it addresses issues of equality and slavery, and the fact it questions how we perceive the world and its inhabitants – both human and animal.

Critics have argued the ship’s exploration represents the emerging modern American nation journeying in pursuit of the white whale symbolising the fledgling country’s yet-to-be-written future.

Into this world Melville introduces the Old Manx Sailor character, “an old sepulchral man” who brings to the ship “old sea-traditions” and “immemorial credulities.” The reader learns the Manxman has studied signs and has “preternatural powers of discernment.”

In this context, the Old Manxman represents in Melville’s mind the Island’s role as an ancient and powerful country. Unlike America, the newly forged democracy, the Island and its native sailor can be seen as a democratic model for shaping a new and emerging American nation. We are told that no sailor on board would dare to contradict the Manxman, and it is significant, perhaps, that on a ship of multiple nations the Manxman is the only character explicitly attributed to a country.

The ancient wisdom that the Manxman brings to the novel is also reflected in his description by Ahab as a “professor in Queen Nature’s granite-founded College.”

In chapter 128, ‘The Line and the Log’, the Old Manx Sailor attempts to measure the ship’s position – long left uncharted by Ahab’s deteriorating mental state. Again, we can see the symbolism of Melville using the Manx nation’s history and political experience as a metaphor for gauging the political maturity of the new American nation.

But in this chapter we find another telling commentary on the Isle of Man. Here Melville has Ahab tell the Manxman he is “too subservient” in failing to share and apply his knowledge. Ahab addresses the Old Manx Sailor directly asking him where he is from.

Answering the Captain: “In the little rocky Isle of Man, sir,” Ahab replies:

In the Isle of Man, hey? … Here’s a man from Man; a man born in once independent Man, and now unmanned of Man”

Melville, with likely exposure to Manx émigrés in the United States, clearly understood the importance of the Island’s history as a once independent nation, with a distinct historical, political and even cultural story. As one of the oldest surviving democracies in the world and with a genuinely dispersed global diaspora Melville uses the Island as central influence in setting the vision of a modern United States outside the gravity/trajectory of British governance. It is this which he draws inspiration from with significant effect in the writing of a Great American Novel.

James Joyce

On the other side of the Atlantic, and about 70 years later, one of the most important, if not most important, writer of the twentieth-century, James Joyce, set out to articulate his vision for a modern Ireland.

Writing autobiographically in his first novel published in 1916, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Joyce’s announces:

“I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.”

Ironically, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, is the only book by Joyce in which the Isle of Man doesn’t feature. In the works that followed A Portrait, however Joyce attempts to forge a new, modern vision for Ireland, evoking the Isle of Man repeatedly.

Joyce knew the Isle of Man and was certainly aware of the two colonies’ shared history and culture - as we will see in his work. When asked in later life if he would ever return to Ireland from self-imposed exile to accept a national honour, he replied that the Isle of Man was as close as he would ever get.

It is possible that Joyce saw the Island as representing a desired shared future for the two countries – with greater independence for Ireland achieved through home rule, a key theme in Joyce’s upbringing and adult life. Home rule was seen as a progressive, ‘third-way’ solution for Irish independence avoiding more extreme nationalism. His family were staunch followers of Charles Stewart Parnell, a moderate Irish nationalist leader and primary mover for Irish home rule.

The Isle of Man first appears in his short-story collection, Dubliners, published in 1914. Here the Island appears in passing references as a destination for tourism and hedonism and as a source of inbound travellers to Dublin.

But the most significant appearances of the Isle of Man are in Joyce’s major works, Ulysses, and his final masterpiece Finnegan’s Wake, where the Island represents the political vision of what Joyce sought to achieve in Ireland.

Published in February 1922, Ulysses reimagines Homer’s Greek epic poem as taking place over the space of one day in Dublin in 1904.

Envisaging his own work as a new modernist epic, Joyce aimed to set out a powerful vision of what a modern Ireland could look like – and, arguably, the Isle of Man plays an important part in this plan.

The most explicit, although not first, reference to the Island occurs in a section of the book titled ‘House of Key(e)s’. Here the novel’s (anti)hero, Leopold Bloom, an advertising salesman for Irish nationalist newspaper, the Freeman’s Journal, attempts to sell an advert to local businessman, Alexander Keyes.

He explains the idea for the advertisement to his friends:

- “Like that, see. Two crossed keys. A circle

- The idea, Mr Bloom said, is the House of Keys. You know, councillor, the Manx parliament. Innuendo of home rule.

As the book unfolds the significance of home rule becomes clear. As Bloom journeys across Dublin he is continually chasing down Keyes to secure the ad sale. Bloom (who is also Joyce’s alter-ego) is literally and symbolically chasing home rule throughout the book.

Not only that, but Bloom’s employer, newspaper, The Freeman’s Journal, has a masthead featuring a sun rising above the heading ‘Ireland a nation’. This is reimagined throughout the book as a shining beacon of a “homerule sun” which, again literally and figuratively guides the novel’s events from sunrise to sunset.

Later in the novel, the House of Keys makes an important re-appearance in a dream-like sequence where, late in the evening, characters make stirring political speeches. Bloom enters this chapter humming to himself ‘London’s Burning’ before telling his friends “a new era is about to dawn” and sets out his vision for a new nation - a “Nova Hibernia” (New Ireland).

John Howard Parnell, brother of the Irish Home Rule leader, appears and tells the crowd: “Illustrious Bloom! Successor to my famous brother!”. He presents Bloom with the freedom of the city “embodied” as “the keys of Dublin, crossed on a crimson cushion” – a symbolic evocation of the House of Keys.

Suddenly, Alexander Keyes, the businessman Bloom has been chasing throughout the novel, yells out: “When will we have our own house of keys?” As the speeches conclude, we are told that “a twoheaded octopus in gillie’s kilts, busby and tartan filibegs, whirls through the murk, head over heels, in the form of the Three Legs of Man”

Although played out with different layers of symbolism, it’s clear that the Isle of Man’s political status and democratic institution is a significant theme for Joyce. Combined with his personal political views it can be argued the Isle of Man and its House of Keys is the living embodiment of a modern and progressive solution for Irish Independence.

In Finnegans Wake, Joyce’s final – and most complex – book, we find once more the Isle of Man, its history and political status littered throughout. In fact, one critic has noted: “The Isle of Man itself seems to be a motif in FW.” The challenge, however, is that finding specific meaning in Finnegans Wake can be difficult as the book is written entirely as a dreamscape in which the main characters dissolve and morph into other figures and objects, using a form of English Joyce invented which builds a dazzling array of portmanteau words from around 60 other languages.

There are many passing references to the Island, in many forms: “isle of manoverboard”; “the ives of Man”; “the calves of Man”; “the Calif of Man”; “the isle of Mun, ah!” (as in Mona); “nor a minx from the Isle of Woman”; “Minxy was a Manxmaid when Murry WOT a Man”; a “Manx Presbytarian”.

We get even more specific references, such as a “Diet of Man” (here, diet refers to a political assembly i.e. The House of Keys); a “Doomster” (Deemster) adjudicates a trial at one point, a “goodrid croven in a tynwalled tub” appears at one point and we even get a slightly smutty reference to “Mona, my own love” and “breastlaw’ (i.e. Manx common law).

In fact, it could be argued that Joyce builds on the modern democratic relationship between between Ireland and Mann evoked through Home Rule in Ulysses by drawing further historic-political connections between the two countries’ shared Norse background.

A good example of this is found in a short verse Joyce used to introduce the third instalment of the book when it was published in serial form:

“Humptydump Dublin squeaks through his norse,

Humptydump Dublin hat a horriple vorse,

And, with all his kinks English

Plus his irishmanx brogues,

Humptydump Dublin’s grandada of rogues”

Here Humpty Dumpty represents the book’s main character Humphrey Earwicker who is rumoured to have committed an unknown sexual infidelity, hence his ‘fall’ from reputable status (also echoing Irish home rule leader, Charles Stewart Parnell’s, downfall). It would seem that this is due to his Anglicised (sexual) preferences, but, in a play on Irishman, we learn that this character speaks with an Irish and Manx accent (or perhaps language).

Clearly, Joyce knows the Island in immense detail and uses this knowledge to bring to life key strands of the book’s narrative – particularly when it comes to articulating modern values, such as sexual and gender equality or fluidity, political freedom or independence and shared culture and histories (the Wake contains strong references to Dublin’s Norse and Viking history, a further connection to the island).

Crucially all these Manx qualities are, in Joyce’s mind, a significant part of our shared history, language and politics. We know this for certain, because a close of friend of Joyce’s, Frank Budgen, has commented that one of the book’s main characters – a “dwyergray ass” who leads four “old codgers” through the novel - represents “among other things, the Isle of Man, once owned by Ireland.”

This is a highly significant point. In the novel the four ‘codgers’ represent (among other things) the four provinces of Ireland, while the name ‘Dwyergray’ symbolically evokes Sir John Grey, owner of the Freeman’s Journal, the nationalist newspaper we encountered in Ulysses with the “home rule sun” rising on its masthead. So, we discover the ass, symbolising the Isle of Man leading Ireland towards an enlightened home rule future.

In addition, it’s important to note that there are two Finnegans in the story’s title: one is Irish mythical giant, Finn McCool, the original ‘founder’ of the Isle of Man (after he scoops out a chunk of earth from Ireland and throws it into the Irish Sea.

Joyce highlights this point in the novel in the lines:

“Yet is it, this ale of man, for him, our hubuljoynted, just a tug and a fistful as for Culsen, the Patagoreyan, chieftain of chokanchuckers and his moyety joyant, under the foamer dispensation when he pullupped the turfeycork by the greats of gobble out of Lougk Neagk.”

This can be translated as: ”is the Isle of Man for him, the giant (Finn MacCool) – formerly the great chief of various tribes, just a tug and a fistful of earth, pulled up from Lough Neagh.”

The other Finnegan in the title is a music-hall song character, Tim Finnegan, who dies and is reborn at his own wake thanks to the revivifying effects of whiskey.

The double-meaning of ‘wake’ is also central to the story: is the book documenting a funeral and end of the Irish nation, or its re-awakening? Giving us a glimpse of what the future may hold for Ireland the novel ends with the wife of the main character urging him to wake up as night turns to day.

This ending powerfully reflects a line from Ulysses which Joyce’s alter-ego utters. He announces: “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake”.

And perhaps this is one good way to interpret Finnegans Wake. Among other things, the book articulates a multi-cultural and multi-linguistic, modern Ireland. One built from Irish (and Manx) mythical foundations, later emboldened by Norse/Viking legal institutions – but ultimately all existing outside of the Roman Catholic and British imperialism he despised.

Conclusions

Returning to the starting point of this essay, it’s fascinating to know that three of the most important literary works of the twentieth-century use the Isle of Man as inspiration from which their authors attempt to shape a future vision of their own emerging worlds.

I want to argue that this is the spirit we need to capture as the Island enters its own new chapter – both domestically, with the incoming administration, and globally with the seismic shifts in geopolitics.

I believe that for the Island to move forward and succeed in new and epic ways, we need to draw on some of the epic imagination distilled in the works of Melville and Joyce.

I argue that their work provides us with fresh perspectives on how important the Island’s contribution to the twentieth century has been and, importantly, can act as inspiration for reimaging our own contribution to the world.

Melville and Joyce, disconnected the Isle of Man from its diminutive status as a minor island off the coast of Northern England and presented it as an influential force in the shaping of new post-imperial nations. It’s time to learn from these lessons of epic imagination and use our unique political, cultural, legal and linguistic history to re-shape our own future.

Gura mie mooar ayd, Simon, for allowing us to publish this piece here.

Recent News

-

Funding for creative Manx language projects announced

Tue, 24 Jun 2025

-

Year of the Manx Language - Gow ayrn, join in!

Tue, 17 Jun 2025

-

Commitment to Manx Culture through Corporate Support

Thu, 05 Jun 2025

-

School celebrated in new Manx film

Wed, 14 May 2025

-

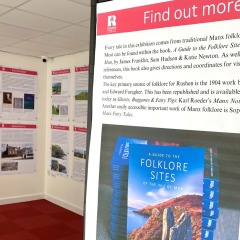

Rushen Folklore Exhibition

Tue, 13 May 2025

-

Manx music in America: This Fair Isle

Thu, 08 May 2025

-

Island Escapes donates £ 5,000 to support Manx Culture

Thu, 01 May 2025

-

Jacob O'Sullivan joins the board

Thu, 24 Apr 2025

-

Folklore Comes to Life Through Puppetry Course

Thu, 17 Apr 2025

-

Manx 'father' of North American

Tue, 01 Apr 2025