The Harvest Queen and her Baby

Mon, 23 Sep 2019

In the ninth in our series of articles about Manx folklore and calendar customs, this piece looks at the customs around one of the most important points in the farming year; the Mheillea. This was recently published in the Manx Independent:

The Harvest Queen and her Baby

September is the time of year for music, feasting, and dancing with the harvest baby…

The harvest was so important in the traditional Manx calendar that the Manx for ‘September’ is ‘Mean-fouyir’ – the middle of harvest.

Large numbers of people were needed to take in the harvest before mechanisation. Teams of men, women and children would work until only the final handful of corn was left.

One of the women, often the youngest of them, was then called upon to act as the Queen of the Mheillea (or Harvest Queen) to cut these last stalks.

The Queen then held this last sheaf aloft to shouts and cheers:

“Hurray for the Mheillea! The Mheillea is took!”

Then came a great feast in the barn laid on for all the workers by the farmer. All manner of hearty Manx food was on offer, from ‘porrage an’ dhry lumps’ to barley bonnags. And, of course, there was always ‘an abundance of strong beer’!

The grateful workers ate well – it’s not by chance that there is a Manx saying, ‘Dy ee goll-rish folder’ (To eat like a mower)!

The pride of place was given to the Babban ny Mheillea. This ‘harvest baby’ was a figure made from the last sheaf. About twelve inches high and decorated with ribbons and wildflowers, the Babban was plaited and tied into a female figure with the ears of the corn as the head.

Dancing to the fiddle was once legendarily popular amongst the Manx, and the Mheillea celebration was no exception.

The benches were pushed aside and the dancing was begun, with the Babban ny Mheillea danced in the Queen’s arms in the middle, or passed around amongst the young women.

The raucous time of ‘reel on reel and jig on jig’ had the fiddler barely able to catch his breath as the dancers were wet with sweat and the women’s ‘ankles clane and calf near bare.’ – But, as George Quarrie wrote in 1880, ‘with jough and fiddles, who cares a fig about tomorrow!’

It would have been late into the night before the celebrations at last drew to a close, and the Babban ny Mheillea was carefully lain on the farmhouse chimney piece. Here it remained for good luck until the next year when the process began again.

Wonderful traditions like this, with ceremonies of queens and babies, have had attempted explanations which point back to pre-Christian harvest gods and rites, but Manx traditions will always elude a final explanation.

However, the next time you are at a mheillea auction, or taking part in the Yn Mheillea dance at a ceili, we hope you might feel a little more connected to this wonderful Manx tradition.

The article will soon be available to be enjoyed on the Isle of Man Newspapers' website.

More about the folklore and customs of the Isle of Man can be found amongst our Manx Year pages.

Recent News

-

Funding for creative Manx language projects announced

Tue, 24 Jun 2025

-

Year of the Manx Language - Gow ayrn, join in!

Tue, 17 Jun 2025

-

Commitment to Manx Culture through Corporate Support

Thu, 05 Jun 2025

-

School celebrated in new Manx film

Wed, 14 May 2025

-

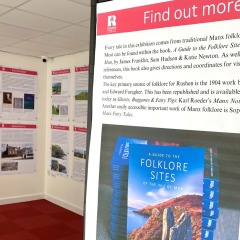

Rushen Folklore Exhibition

Tue, 13 May 2025

-

Manx music in America: This Fair Isle

Thu, 08 May 2025

-

Island Escapes donates £ 5,000 to support Manx Culture

Thu, 01 May 2025

-

Jacob O'Sullivan joins the board

Thu, 24 Apr 2025

-

Folklore Comes to Life Through Puppetry Course

Thu, 17 Apr 2025

-

Manx 'father' of North American

Tue, 01 Apr 2025